Strengthening community through placemaking

By Uma Peters, Community Member

3 min read: Community member and 8th Grade Graduate of Linden Waldorf School, Uma, was required to choose a year-long project that is focused on learning a new skill based on what we are interested in as our career. Her goals were to design a solution for community issues while being environmentally sustainable. She chose Elizabeth Park in North Nashville to focus her work.

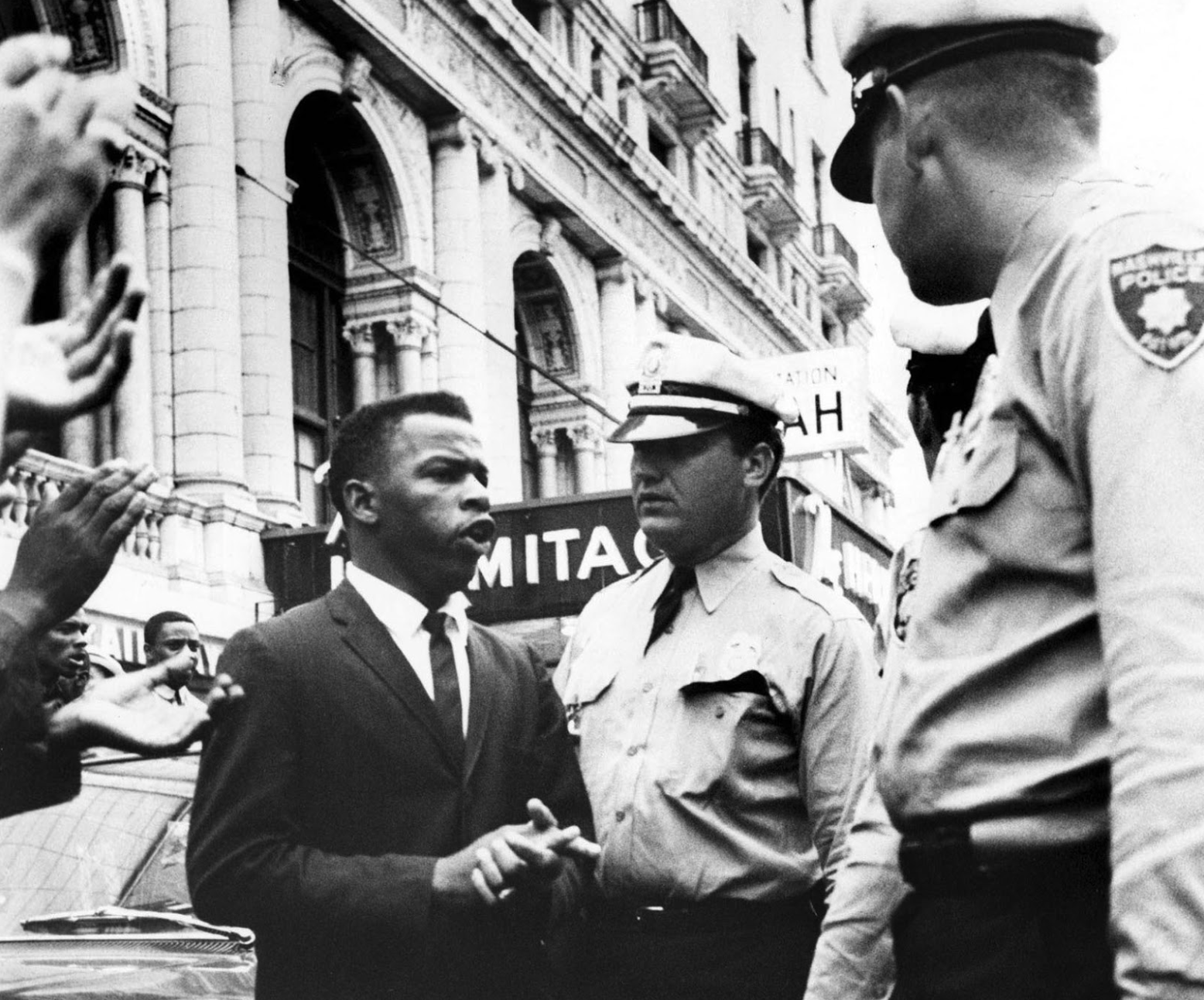

White flight and redlining, public housing issues, and gentrification are all factors that play a part in the history of urban planning and are things we must take into consideration when we are designing for communities. “White flight” refers to the mass migration that occurred between the 1960s and 1970s when White people left urban city centers for the suburbs. The goal of white flight was to separate White and Black schooling and residential areas. Because of the stereotype that Black neighborhoods and Black people were dangerous, there was a mass exodus of White families to suburban areas. Redlining, or refusing a loan or insurance to someone because they live in an area deemed to be a financial risk, contributed greatly to white flight because whites began to be told by banks and realtors to leave mostly black neighborhoods that were redlined. Redlining first started in 1934, when the Housing Act of 1934 was established during Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s presidency, where they claimed that the purchase of a home by an African-American family in a White neighborhood would cause the value of the White-owned property to decline. Public and affordable housing issues have existed for decades, but are often ignored. The federal public housing program started as part of the Housing Act of 1937. The Housing Act of 1937 was originally established to clear slums. However, it ended up being made to segregate neighborhoods, and the federal government often supported the local governments’ policies to do so. These are all things that played a part in segregating neighborhoods and people, and things that affect communities even today.

Students C.T. Vivian, Diane Nash, and Bernard Lafayette lead a 1960 march in Nashville. [U.S. National Endowment for the Humanities photo, public domain]

Nashville is a city that has experienced all of these factors, and currently is undergoing gentrification across many areas of the city (East Nashville, North Nashville, the Nations). Nashville has experienced significant changes in the housing market, population, household income, and demographics in the past few decades, and it has become the 10th fastest growing city in the United States. As Nashville continues to grow, housing prices will continue to rise and neighborhoods will continue to be revitalized. Many existing residents have not seen their incomes rise to keep up with the soaring costs of housing, and they constantly have to fight off developers (daily calls, daily mail, in-person visits) who offer below-market prices. It is also very important, however, to find ways of improving communities without driving out existing residents or continuing to segregate them. Nashville must build strong community partnerships with existing residents who have a voice in how communities are developed, while still preserving its history.

My name is Uma Peters and I am 14 years old. I am doing a project on the topic of urban planning, and my goal for the project was to design a solution for a community in need. My inspiration for this project started when I met John Lewis in Washington D.C. John Lewis went to college at fisk university, which is in North Nashville. He organized lunch sit-ins in Nashville to push against segregation and Jim Crow laws.

John Lewis (later elected to the U.S. House of Representatives) talking to Police around the time of Nashville Sit-ins (1960).

I was inspired by his civil rights movements and action for social justice, so I wanted to find a way to incorporate social justice and design into a way where I could help a community. I ended up choosing Elizabeth Park in North Nashville as my location. North Nashville is an area in Nashville that used to be a very thriving Black neighborhood, but when Interstate 40 was built in 1957, it was built right through the main street of North Nashville, Jefferson Street, and destroyed many restaurants, nightclubs, homes and venues that had helped the neighborhood thrive. Mainly Black communities, like North Nashville, tend to not have easy access to banks, grocery stores, transportation, or schools. Mainly Black communities also tend to lack access to amenities that make communities more livable, such as parks, playgrounds, sidewalks.

The map above shows the location of Elizabeth Park

North Nashville is now starting to be revitalized, so I wanted to design something that would benefit the existing residents without contributing to the problem by raising prices and forcing them out. I started by making surveys for the community, so I could have feedback from the residents themselves. From there I started to come up with designs for the space, and then made a second survey for people to vote on the designs. I ended up choosing to do a community space with a few garden beds and an ivy wall.

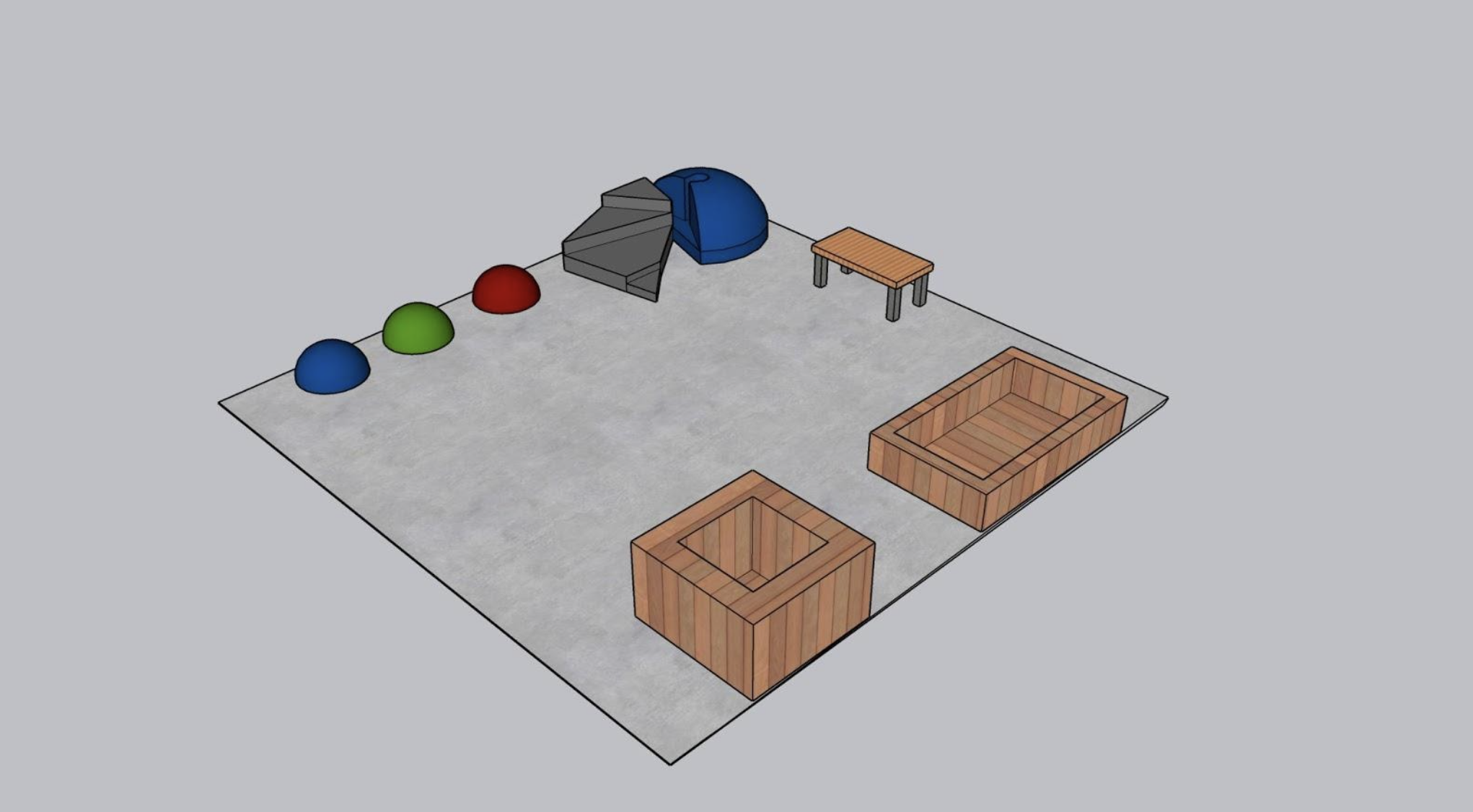

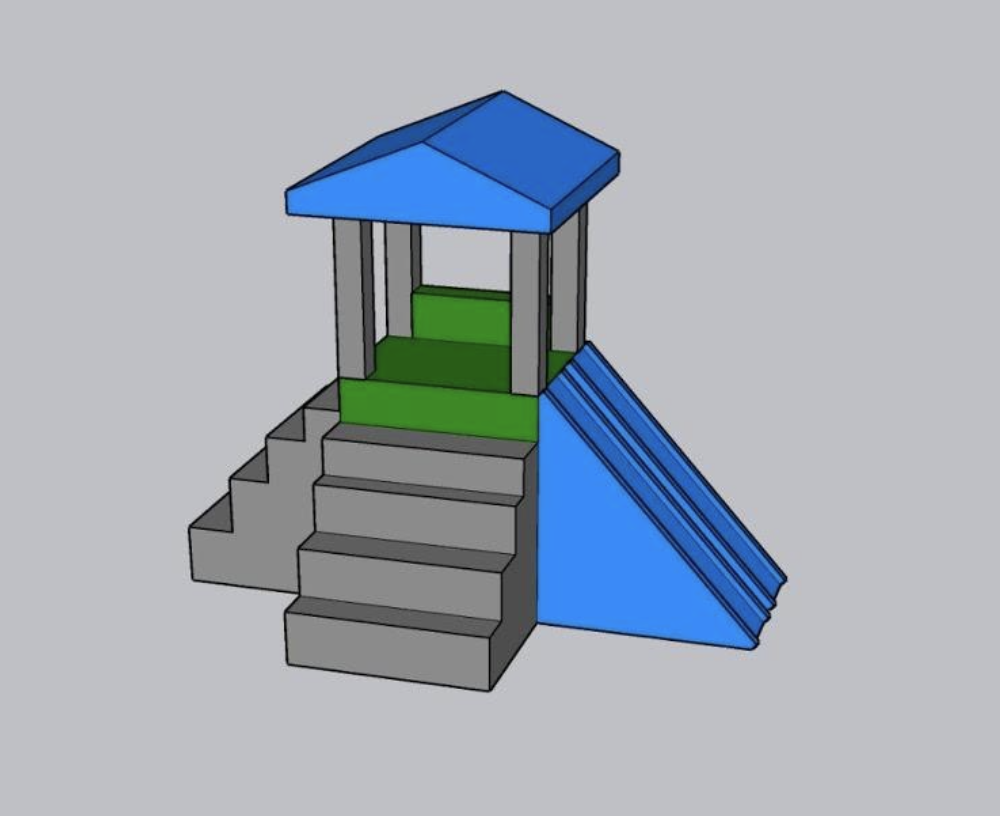

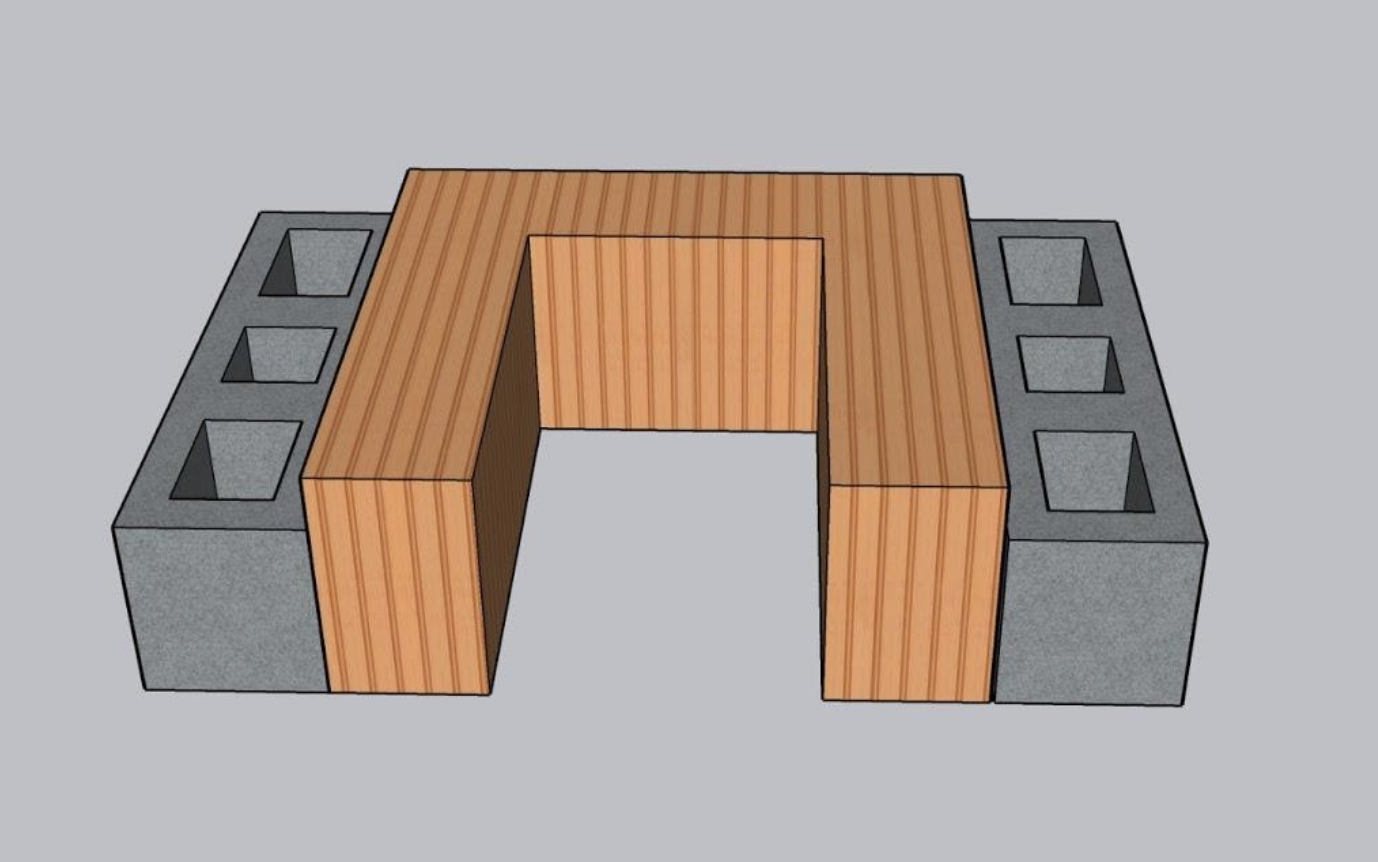

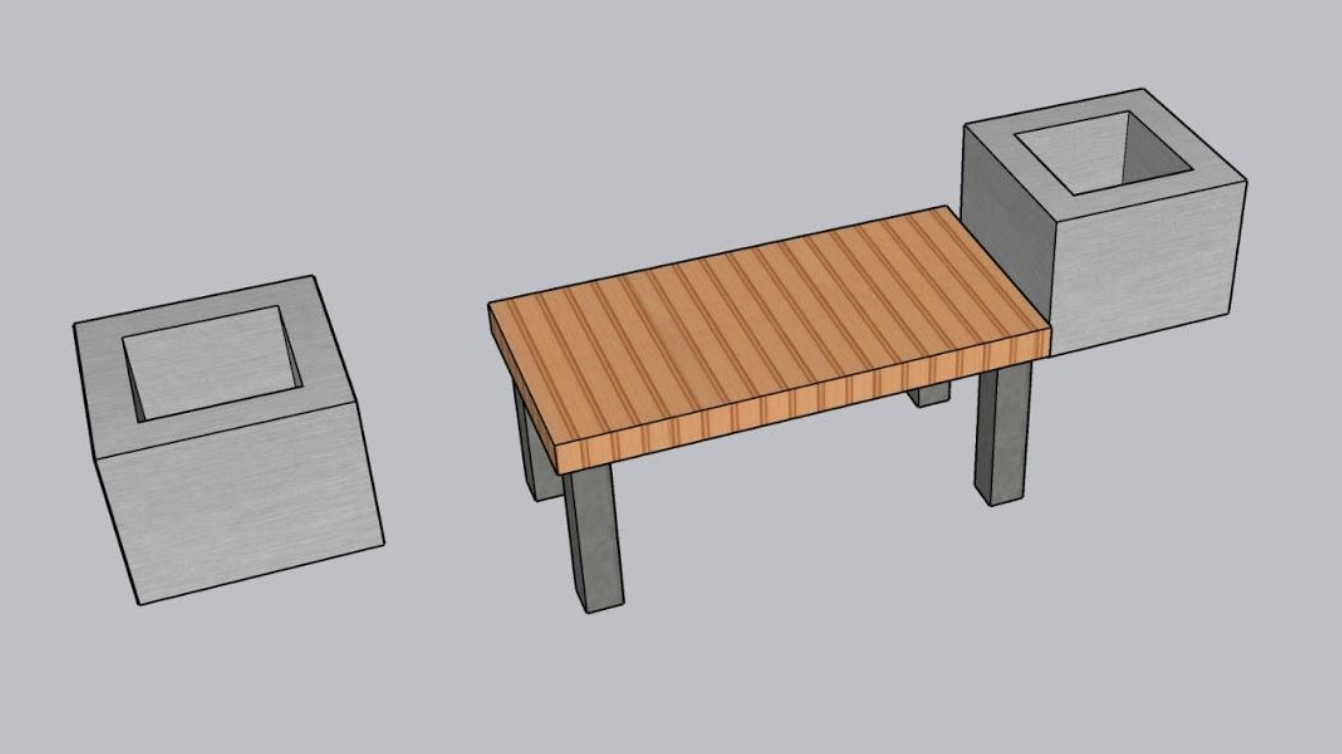

Elements that could help activate Elizabeth Park

I have made a 3D model of my design, and plan to reach out to community partners to help make this a reality. I would also like to give a big thanks to Eric Hoke, for mentoring me throughout my project. If you are interested in supporting this idea/project feel free to take the surveys linked down below.

![Students C.T. Vivian, Diane Nash, and Bernard Lafayette lead a 1960 march in Nashville. [U.S. National Endowment for the Humanities photo, public domain]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ec82e4c1b61ca5861c6d51c/1624387250930-50CT4CU05TVDKPH5I1UT/1_TfeuR4bjpJxVD_2BYQPmhw.jpg)