East Bank of Tomorrow

By Veronica Foster, Communications and Advocacy Manager + Taylan Tekeli, Design and Research Assistant

25 min read The following blog outlines the history of the Civic Design Center’s visions for the East Bank neighborhood in Nashville. We discuss specific reasons why 2022 is a turning point for riverfront development in Nashville, and how we can continue to dream big about the future of the East Bank neighborhoods for local Nashvillians. We showcase precedents and conceptual designs that carry out community member visions, and discuss Metro Nashville Planning’s newly released Imagine East Bank Draft Vision Plan. The timeline of this has been aligned with the release of the report so community members can provide effective public feedback during the open comment period.

If you missed the Urban Design Forum on 8/22 where Planning first presented their Draft Vision Plan, you can watch the recording here.

New Neighborhoods with Critical Connections

Circa 1908 figure ground representation of East Bank. Once a largely residential neighborhood with industry on the riverfront (The Plan of Nashville).

Nashville’s East Bank of the Cumberland River is critical to the mindful growth of the city for the next 10-20 years. If this area is finally rebuilt into the neighborhoods it has the potential to be, we may just fulfill one of the most major master plan connections that was formulated in the Civic Design Center’s founding book, The Plan of Nashville. In short, the area could be transformed from an industrial, parking lot wasteland into a number of thriving Inner Loop neighborhoods.

Since the period of Urban Renewal, neighborhood transformation was seen as “progress” for the privileged, but it usually resulted in the devastation of cultural identity and the displacement of community members. In the early 20th century, the East Bank was a neighborhood with a fine-grained street grid, but between natural disasters, the creation of the interstate in the 1960s, and redlining, the only thing that is recognizable is the industry that partially remains.

It isn’t often that cities have the opportunity to create neighborhoods from a high concentration of publicly-owned land without displacing people who already live there. Sadly, it’s been a long time since this area has been a cohesive neighborhood, so new development of the East Bank will push us to recreate its identity from scratch, while hopefully displacing 127 acres of asphalt that should no longer occupy such central, valuable real estate.

We’ve been thinking about this for 20 years.When the concept of New Urbanism became popular and the idea of the Civic Design Center was just starting to take shape in the late 1990s, connections over the river became more and more important. Bridgestone Arena was built Downtown, and Nissan Stadium, originally called Adelphia Coliseum, was first built on the East Bank shortly thereafter. Our original founders were a part of an advocacy effort to redesign the proposed highway-like road that was intended to support the traffic produced by these high-capacity event centers. Learn more about the history in our Origin Story Video.

Eventually the highway-like design was pared back into an “Urban Boulevard” design with a roundabout terminus (now Korean Veterans Boulevard), and concepts like this were replicated in The Plan of Nashville’s community vision for the East Bank, imagining what the area would look like if the highway was replaced with an urban boulevard (demonstrated in the images below).

In 2012, the Civic Design Center hosted an international design competition focused on the East Bank, called Designing Action. The competition specifically requested that health in the built environment be considered, especially due to the impacts of the 2010 flood, which reminded Nashvillians of the care that must be committed to the 500-year floodplain on the East Bank.

While The Plan of Nashville’s vision for the East Bank was more about creating a mixed-use urban village and the Designing Action competition visions focused mainly on creative public-space design, the housing crisis in Nashville is pushing us to think denser in 2022. Our city is growing, and with such an important, nearly blank slate of developable land comes huge opportunity.

Why is this critical right now?A lot of things are coming to a head in Nashville 2022.

The Christmas Day bombing of 2020 made us consider not only the restoration of Historic 2nd Avenue, but also our connections to 1st Avenue along the Cumberland. While currently 1st Avenue is treated more like an alley, community members are eager to see Nashville focus on revitalizing the Downtown Riverfront.

In the last year, a lot of other Riverfront developments were announced that would bring greater attention to reconnecting to the Cumberland, especially in Inner Loop Neighborhoods. Those include River North, The Riverside in Bordeaux, and Wharf Park.

Since launching Imagine East Bank in February 2021, Metro Planning has held numerous public meetings, over 150 technical meetings and a number of online surveys for a study area that is 338 acres of public and private land. Metro Planning has just released the Draft Vision Plan for public comment.

In early 2022, it was announced that the current Nissan Stadium is not necessarily worth repairing, and there has been a proposal for the State to subsidize the construction of a brand new Titans football stadium on the East Bank. The proposal would raise the hotel tax 1% to fund construction. The Titans’ CEO, Burke Nihill, stated at the Business Journal Stadium Debate on July 22nd that if the new stadium is not built, then the existing surface parking must remain undeveloped for the next 17 years. However, land lease negotiations are currently underway, so the decision has not been formally announced. While we don’t have ears on the exact nature of the negotiations, the Titans are making their stance clear to the public.

Ultimately, it’s important to know that the Imagine East Bank Draft Vision Plan is not contingent on the final stadium decision that will be announced in November 2022. The Draft Vision Plan showcases two alternatives for the design, 1) where the Stadium is rebuilt in its proposed location across the street and, 2) where the Stadium remains in its current spot.

There is a housing stock and housing affordability crisis in Davidson County. The US Annual Inflation Rate rose to 9.1% in June 2022, and the Housing Inflation Rate is up 5%.

Much of the East Bank is under a Mixed Use Intensive (MUI) zone code meaning there is higher allowable density than currently exists in this area. It also has an MDHA East Bank Redevelopment District overlay which will likely include development incentives and more design requirements.

Public Comment Period on the Imagine East Bank Visions will be open from August 22, 2022 to September 16, 2022, please review and comment now!

Our visions for the East Bank touch on nearly every Guiding Principle that we strive for, but our greatest focus for this blog will be on representing the community’s ideas, envisioning a well-connected transportation network, and evaluating the feasibility of these visions with recommendations for the Request for Proposal (RFP) Process.

Creating a Unique Identity for the East Bank

Within this section we will discuss the desired East Bank development programs. The following images represent either precedents or programming visions for the East Bank neighborhoods, from housing to restaurants, retail, and more! Many of the images used are visions created by UT Knoxville architecture students. The Civic Design Center partners with the UT Knoxville architecture program through an Urban Design course where students explore sites across Nashville, and how they impact Nashville's urban fabric.

Click the icons below to jump ahead and review a specific section.

The East Bank is like a young person entering high school. There is great opportunity to reinvent their identity leaving behind the embarrassing growing pains of grammar school. However, they are still in their hometown, so a few people will remember who they used to be—maybe using it as a judgement against who they want to become.

Based on a community engagement survey* conducted by Stand Up Nashville, there are serious concerns about the East Bank’s identity. The East Nashville area surrounding residents are worried that the East Bank will become an extension of Downtown, drawing tourists into greater East Nashville which has historically been a refuge for local residents. Note that nearly 75 % of the perspectives from the survey are greater East Nashville residents, but the neighborhood will hopefully have graduated building heights and programs that toe the line between the surrounding East Nashville neighborhoods and Downtown. Ideally, we would like to see medium to high density residential developments that could support that character.

*The survey was called “The Future of East Nashville”, and had a total of 164 respondents.

“A Community Benefits Agreement can sometimes be the only tool available to ensure these kinds of benefits come to fruition, especially in a state like Tennessee that has laws on the books that tip the scales in favor of developers and corporations.”

A whopping 84% of survey respondents would like to see the East Bank become “a walkable neighborhood with affordable housing and independent businesses”. Below, you’ll find some diagrams that outline various visions of land-uses and programs for the future neighborhoods.

Ultimately, most respondents didn’t want the focus on a potential new football stadium; only 8% of respondents wanted the East Bank identity to be entirely a “sports entertainment district with many dining and hotel options”. 85% of respondents were against using public dollars to fund a new stadium, but when considering a “Community Benefits Agreement that protects workers, builds affordable housing, and supports small businesses”, respondents were significantly more open-minded.

We asked Stand Up Nashville to tell us about Community Benefits Agreements, and how they can advocate for what the community wants in the East Bank.

A real Community Benefits Agreement (CBA) is a binding deal between a developer and a nonprofit organization that requires the developer to include lasting beneficial infrastructure in a new development. Examples of benefits include affordable housing, small business incubation space, giving first dibs to minority contractors, local hire, living wages for all workers, and strong construction safety standards. CBAs uplift communities because they provide lower housing costs to keep working-class families in the city, opportunities for minority-owned small businesses and contractors to succeed, and good wages for local workers. With developer cooperation and strong enforcement from the nonprofit entity, a CBA can sometimes be the only tool available to ensure these kinds of benefits come to fruition, especially in a state like Tennessee that has laws on the books that tip the scales in favor of developers and corporations.

In 2018, Stand Up Nashville won a historic CBA on the MLS soccer stadium project. This monumental victory shows that large developments can be done with high standards and the community at the center of the process. Some of the things they advocated for and won were 20% new units designated affordable housing, sliding scale childcare facility, and contractor safety regulations.

In the Imagine East Bank Draft Vision Plan, we especially appreciated the Neighborhoods for Nashvillians section, outlining key neighborhood catalysts and development guidance that will hopefully be significant in influencing the East Bank’s identity. The section maps areas that Metro Planning will be focusing on like streetscaping, transit, and parks, while identifying the building objectives for land lease development. They focus on the significance of lower floors and scale, but they do not go into the potential programming for those built forms. The following sections outline community-based recommendations for building programs.

Medium-High Density Affordable HousingThe East Bank study area is a whopping 338 acres large and includes 100+ acres of publicly-owned land, which is what gives tax-payers the leverage to advocate for what they want. Metro Nashville can lease the land to developers with major stipulations, and affordable housing is the most overwhelmingly requested land-use program from the public.

“Advance equity, resiliency, and high quality of life for all Nashvillians through the creation of accessible and affordable places to live, work, and play.”

With rising costs of materials and labor as well as the immense value of land on the East Bank, it will take extensive advocacy to ensure that Metro Nashville is holding up their commitment to equity. We believe that following through with extensive affordable housing stipulations is critical to atoning for historical displacement on the East Bank. Planning states specifically in their Draft Vision Plan that economic analysis points to many challenges, but “an inclusive approach to developing the East Bank can help meet some of Nashville’s large and growing affordable housing needs.”

The housing concepts in the East Bank do not have to fit the traditional mold. A recent atypical affordable housing development, Martin Flats in Wedgewood Houston, focuses on well-designed micro housing to accommodate 1-2 persons in studio units with amenities and furnishings included. On the other hand, “Musical Living” is a conceptual design by University of Tennessee Knoxville student, Mars Seay. Their idea includes a public library with civic space, and housing above. This type of innovation could be possible if Metro leased air rights to a developer to who could build housing on top of a public building.

If we really think outside the box, we could create an interactive affordable housing experience like the 1st prize winner of the London Affordable Housing Challenge. Their concept uses innovations in 3D printing to create truly adaptable, self-imagined and self-built housing structures—talk about participatory design!

Martin Flats micro-housing in Wedgewood Houston

“Musical Living” combination civic-housing concept in its exploded circulation view, click to enlarge

Locally-Driven Restaurants and RetailBoth in the Stand Up Nashville Survey and the Imagine East Bank survey results, community members insisted they did not want the East Bank to feel like an extension of Downtown or a mirror of the Gulch. We believe that the retail programs within the mixed-use developments on the East Bank will be an essential opportunity for crafting that unique identity.

“Create vibrant livable, and authentic neighborhoods that prioritize the everyday needs of Nashvillians.”

A much lower scale, but interesting precedent, is The Wash in East Nashville’s Eastwood neighborhood. The Wash provides alternative options to chefs and restaurant owners who may not want to (or be able to) invest heavily in a permanent, conventional space. Ultimately, the space provides lease options for micro kitchens within an outdoor food hall experience that is more likely to attract local businesses, rather than well-established restaurant chains. Additionally, its distinct lack of parking options may encourage more neighborhood visitors or those willing to take the bus to spend time in the space.

Fifth and Broadway, on the other hand, is a Downtown restaurant and retail development that also has dozens of local or small chain restaurants in their Assembly Food Hall. This is in addition to local as well as major chain retail on the ground floor. Because the East Bank will have an identity between East Nashville and Downtown, finding a happy medium between these two precedents would be a great direction to consider.

The Wash

Fifth and Broadway

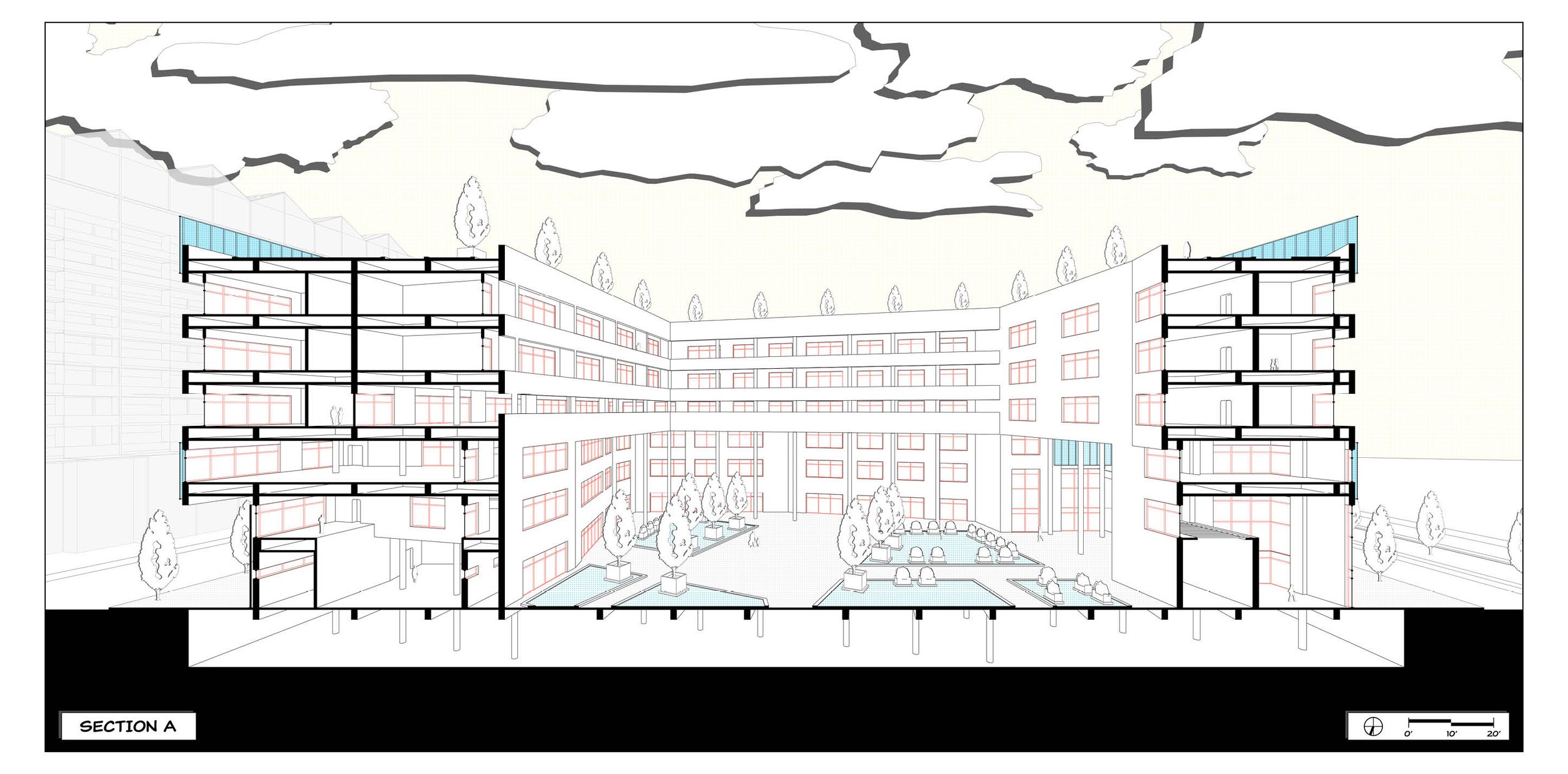

Office SpaceUTK architecture students envisioned the East Bank as Amazon’s potential HQ2 in 2018

Office space on the East Bank isn’t so much desired as it is inevitable. With the neighborhood’s access to downtown and the desirability of office spaces with a view, we are likely to see high-rise office buildings. To make sure the neighborhood identity feels separate from Downtown, we are looking for office development that breaks the mold of the shear high-rise facade. Instead of a gated office campus, we would like to see mixed-use office buildings that integrate more into the character of the neighborhood. Retail ground floors and open balconies could make it feel more like an urban center rather than a commercial downtown core.

We wanted to showcase the visions for the newly-approved Google campus in Downtown San Jose, CA as a precedent. The office campus has a major sustainability focus, touting solar energy and a microgrid that will make the campus net-zero. It will include around 17% affordable housing units, a vast public space network and a 1.5 acre Creekside Walk. There’s a lot of good that can be done getting creative with office developments, especially in a location that is sure to be an excellent draw for employees.

Google’s Downtown West campus master plan

A rendering of what Google envisions for their campus’s public space components

Mindful HospitalityThe Gallatin Hotel Lobby

While the East Bank currently hosts zero housing units in the area, there are already 4 major hotels. While community members are not interested in the East Bank catering to the tourist population, there may be ways to incorporate hotel developments that give back something to the community. The Gallatin Hotel, an adaptive reuse development of an old church, decided to honor the concept of “love thy neighbor” by sharing a portion of their profits with local causes. Some of East Bank hospitality projects can develop a similar business plan to the Gallatin Hotel to provide surrounding non-profit programs (such as affordable housing or business incubators for immigrants) with a portion of their profits or direct resources.

Another way to design a hotel that is scaled and oriented towards the neighborhood would be to focus retail or restaurants on the ground level. Like the Chicago Athletic Association Hotel, an architect may consider designing the building with the hotel lobby on the 2nd level, so that the ground level can remain fully accessible to the public.

One University of Tennessee Knoxville student, Keith Carter, created a concept for a “Titan’s Tower”, which would include a hotel and office space. The idea would connect tourists visiting for a football game directly to the stadium, so that vehicle traffic on Game Day could be significantly reduced.

“Titan’s Tower” concept program view

Diverse Cultural AttractionsStand Up Nashville’s Real Community Engagement on the East Bank Report showcased what residents hoped could create East Bank’s cultural identity

There are many other ways to craft East Bank’s identity, which is why we wanted to showcase visions from other architecture students at the University of Tennessee Knoxville. Their visions include other unique programming ideas that might be outside of the box, but offer something distinctly “East Bank". For example, the students crafted ideas like an urban farm housing development, a climbing facility, an aviary museum, an international center, and a maker space. Scroll through the gallery below to get inspired by their unique ideas.

Revisiting the Urban Boulevard and Deprioritizing Highway Access

This section includes information from the Imagine East Bank Draft Vision Plan, but also refers to more conceptual ideas that our Design Studio has created as food for thought. We will focus in on imagining the street network and its multimodal uses, the conceptual mobility hub, and finally public space. Click the icons below to jump ahead and review a specific section.

Beyond developments’ programming that could formulate the East Bank identity, the street network for the neighborhoods will be critical to the future of multimodal transportation in Nashville. In this area, Nashville is lucky to be starting from scratch rather than retrofitting existing roadways that don’t offer transit, or safe walking and biking infrastructure. While we are starting from scratch, Metro Planning essentially provides a disclaimer at the beginning of the Imagine East Bank Draft Vision Plan stating that they will be working hard with Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT) to acquire public-right of way included in their plan.

Metro’s Draft Vision Plan East Bank Boulevard rendering shows Bus Rapid Transit, two lanes of traffic in each direction, large sidewalks, and intermittent loading zones

Lucy Kempf, Metro Planning Executive Director, opens the foreword of the Imagine East Bank Draft Vision Plan explaining, “a place of contradictions, the East Bank is centrally located within a thriving city, but is perceived and experienced as an island.” The Draft Vision Plan includes two major changes that would weave the island-like area back into the fabric of East Nashville. Since the East Bank currently has no continuous connections, the Draft Vision Plan focuses on a North-South spine street that would follow the geography of the River. That is currently visioned as a boulevard-style road with Bus Rapid Transit along the median, two traffic lanes on either side, and a generous sidewalk. While there is not currently a bike lane in the vision for the boulevard, Metro Planning has chosen to prioritize bike lanes on a parallel road, and complete the greenway directly alongside the Cumberland.

The Draft Vision Plan shows implementing new Collector-Distributor roads to eliminate highway access in the East Bank

Another change that could facilitate better connections is the plan to work with TDOT to remove the Main Street and Woodland Street highway entrance/exit ramps, facilitating less thru-traffic in the East Bank neighborhood and encouraging more local traffic in the area. While this isn’t The Plan of Nashville’s 4-Step Plan to Removing the East Bank Highways, we intend to fully advocate for this vision to remove the highway access in this area.

There are a number of other important changes that will require collaboration between TDOT and Planning, like completely overhauling the James Robertson Bridge and adding additional bridge connections across the Cumberland. They intend to overhaul the Ellington Parkway arrival, aka Spaghetti Junction, and reroute the railroad that runs along the Parkway. Planning will also be continuing to study the terminuses of the North-South boulevard, so there is still a lot of room for other street connections.

An interesting observation around the potential removal of highway ramps and rerouting rail is that this Draft Vision Plan takes away 2 of 3 preferred transportation methods (the 3rd being water barge) for the industrial site occupied by PSC Metals/SA Recycling. This effectively takes a stance to deprioritize industry on the East Bank and we are all for it.

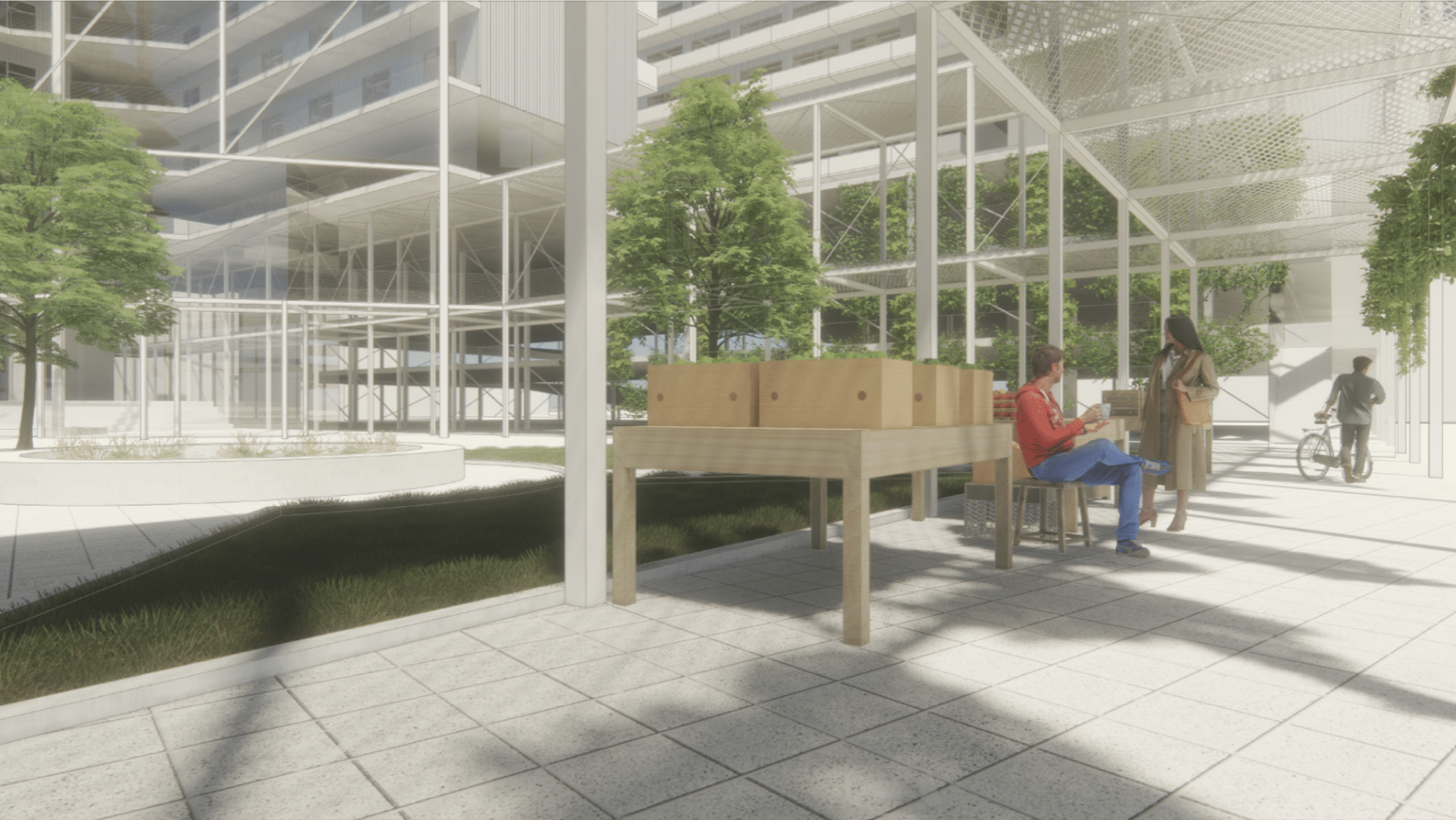

Street Network and Multimodal UseThe Organic Nexus concept uses meandering streets at ground level, encouraging developments to use a second level of privately-owned public bridges and plazas

Since the Draft Vision Plan is not final at this time, we also wanted to share our own bold, conceptual idea for an “Organic Nexus Boulevard” that would break the mold of a traditional streetscape. The Organic Nexus Boulevard looks to create a more unique central spine for the East Bank.

Within the Nexus we conceptualized organic streets that weave into the sidewalks and park space. The Boulevard itself becomes a mobility hub that encourages a variety of transportation options. By morphing sidewalks/parks into the streets we are able to create dynamic routes that flow, curve and break out of the traditional straightaway design. Imagining the future of autonomous vehicles, we can safely invest in the concept of free flowing streets.

With the Organic Nexus concept, we looked to the past when streets were shared freely by all modes of transportation. When the street becomes the epicenter of activity for pedestrians, it makes them a crucial part of the neighborhood’s social interactions. This truly breathes into our Guiding Principle, Celebrate streets as places that address neighborhood needs and facilitate community interactions. One of the associated goals of this principle is “mode equity”, meaning that the most accessible transportation option is prioritized.

We asked Walk Bike Nashville to tell us what their ideal multimodal East Bank Boulevard looks like.

Metro’s Draft Vision Plan shows the potential bicycle network with a riverfront greenway, and protected bike lanes on 2nd Ave, but lacks bike lanes on the boulevard.

The ideal vision for multimodal infrastructure is one that makes it desirable and safe to move through the new neighborhood without the need for a car. It is concerning that the current plans do not have bicycle infrastructure on the Boulevard when community members prioritized bikeability and walkability in the Imagine East Bank’s Multimodal Survey, naming "provide more spaces to walk and bike" as the top design preference for the Boulevard. The inclusion of protected bike paths on the Boulevard would not only enhance accessibility to retail and residential destinations, it would set a standard for Nashville's streetscape, demonstrating that all users truly are welcome on our streets.

Ultimately, when drivers of personal vehicles must pay attention to complex road stimuli, they are more likely to drive carefully. Bike lanes would not only enhance the user experience, but they would actually contribute to a safer pedestrian experience.

Beyond the Boulevard, we are hopeful about the redevelopment of East Bank offering a greater network of multimodal connections from East Nashville into Downtown and vice versa. Woodland Street is a huge opportunity area where restriping the street from Five Points across the Woodland Street Bridge into Downtown to include protected bike lanes would transform bike commuting. By removing the highway ramps at Woodland, it would be an even safer cycling corridor. Below, you can see the visions we created on behalf of a community member’s idea for Woodland Street Bridge.

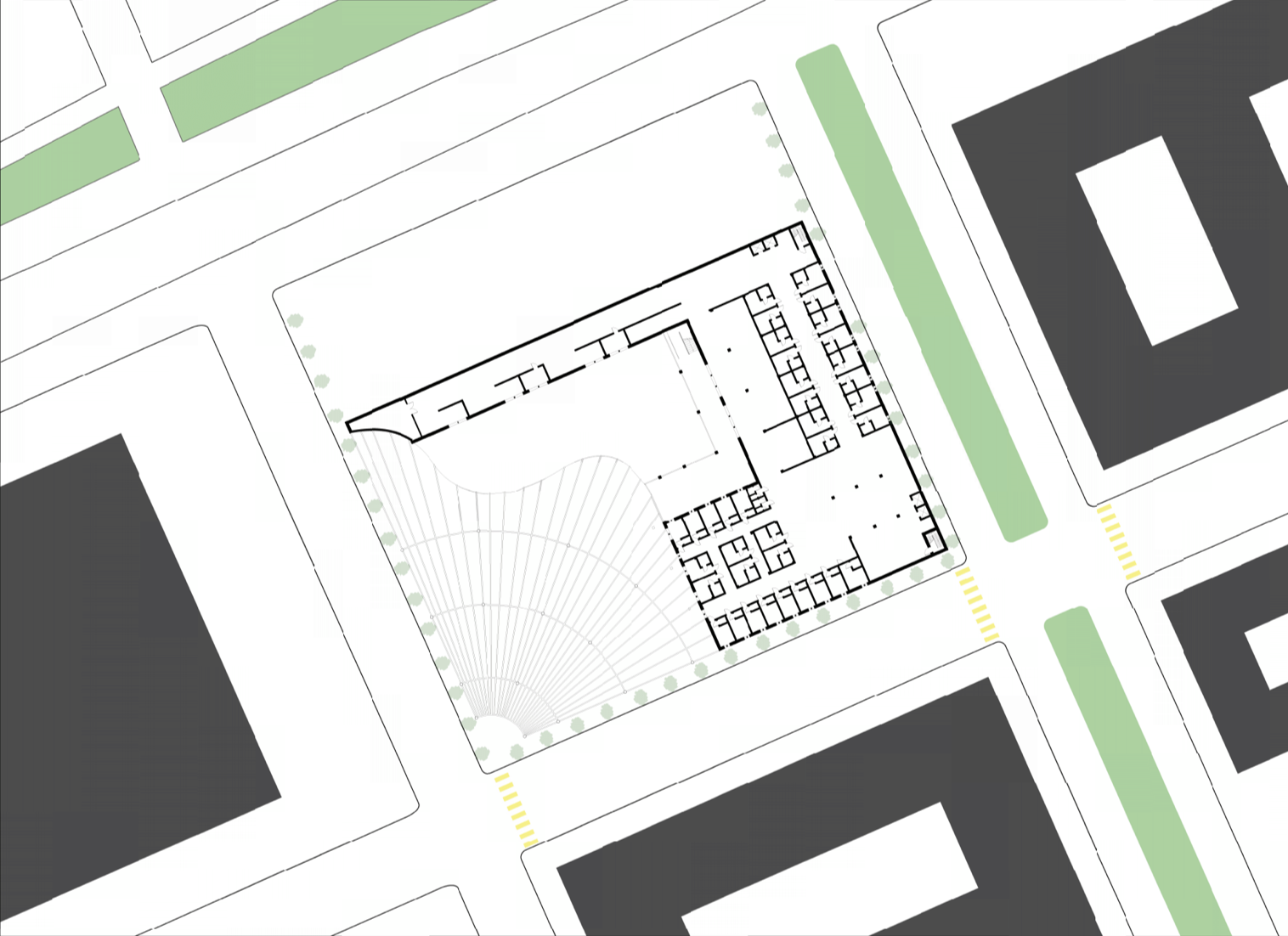

Mobility Hub and Transit ConnectionsEast Bank Mobility Hub vision by UTK student, Kinna Dutton, which also includes housing

Interior perspective of a East Bank Mobility Hub vision by UTK student, Kinna Dutton, which also includes housing

An essential part of creating a collection of high-density neighborhoods on the East Bank is prioritizing transit. As Nashville’s population continues to grow, personal vehicle commuting is going to be less and less convenient. The current East Bank landscape contains thousands of surface parking spaces and beyond the use for Nissan Stadium events, a fair amount of Downtown employees park in a parking lot on the East Bank and either walk or take a private shuttle over the Cumberland to their office. People are going to have to start changing their commuting habits, and it’s about time.

Civic Design Center diagram that outlines the connections between current and planned Mobility Hubs

We are very excited about the Imagine East Bank Draft Vision Plan’s inclusion of a true multimodal Mobility Hub. Metro Planning describes the vision for the Hub as being smaller than the Elizabeth Duff Transit Center at WeGo Central and larger than Hillsboro Transit Center. We agree with this direction, making sure that primary commuters stay on course through Downtown, but we believe that the East Bank is a great opportunity to connect East Nashvillians to other neighborhoods without having to go through Downtown, and vice versa. With the East Bank Mobility Hub, we would also complete the Downtown circuit, alleviate the pressure from the Duff Transit Center, and connect to the future SoBro Mobility Hub as shown in Nashville Next’s InMotion.

Flyer from the Affordable TOD Urban Design Forum from April 2019

This is also a big move for Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) for people will will live, work, or play on the East Bank. The more convenient transit is, the less people will need to use private vehicles. Our foundational Guiding Principle, Develop an equitable and desirable transportation infrastructure, specifically focuses on the word “desirable” because that equates to a well-kept, convenient, efficient and preferred transportation system.

Leasing air rights over public buildings is a huge opportunity for TOD in Nashville because transit and housing are extremely interconnected. EOA Architects’ initial design for the Duff Transit Center included housing above the terminal, which was unfortunately not deemed a priority when it was first built. In 2019, Vanderbilt Engineering students did a feasibility study reopening the discussion of housing development on top of the Duff Transit Center, which also included a study for using mass timber to complete the project more sustainably. This past Spring, University of Tennessee architecture students included a mixed-use Mobility Hub in their East Bank Master Plan.

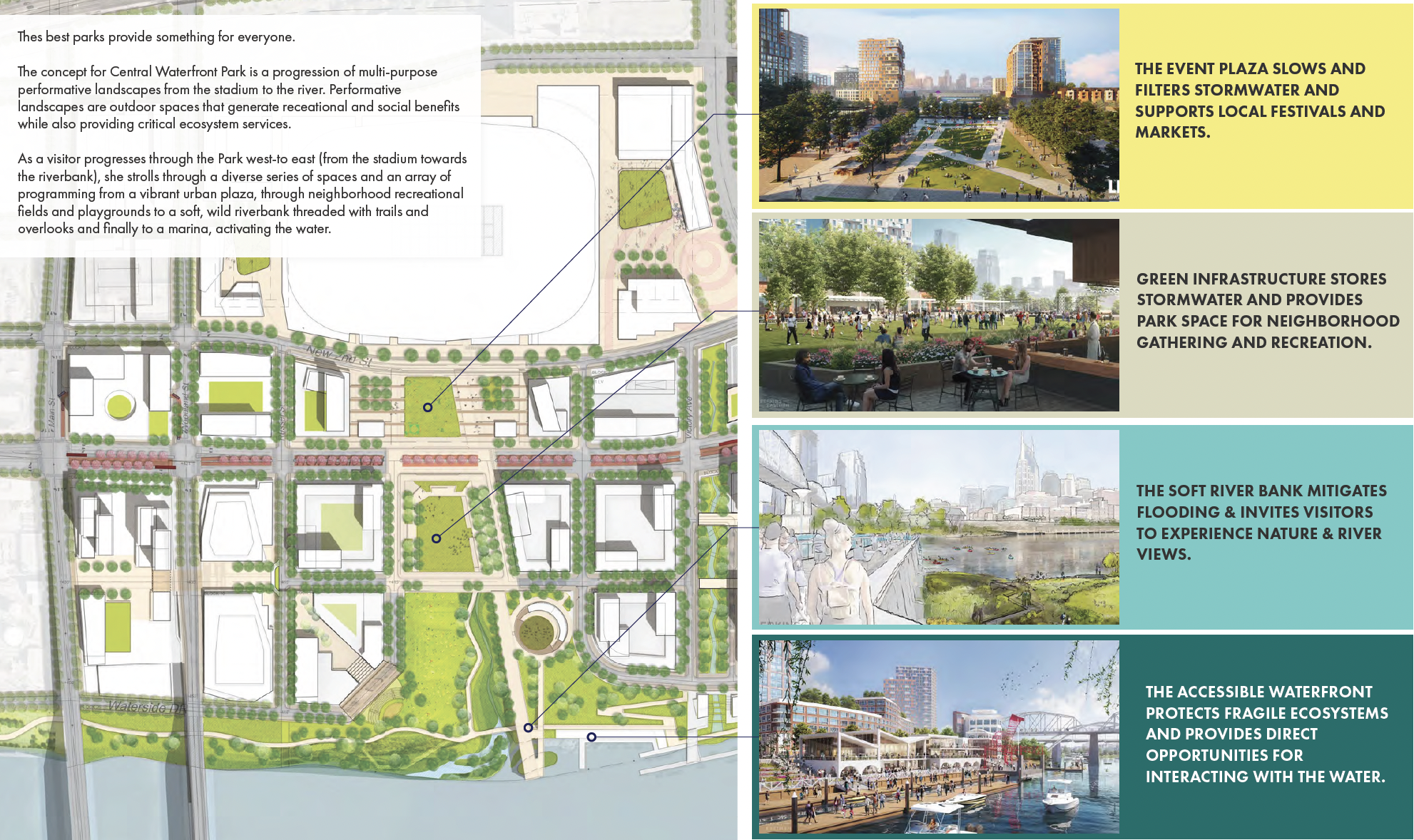

Public SpaceArea in blue shading identifies the FEMA Floodplain area of the East Bank

A significant amount of the East Bank falls in the 500-year flood plain, which means that every year has a 0.2% chance that flooding will reach maximum levels. While this sounds fairly unlikely, flooding has the possibility to destroy homes and businesses, displacing community members and litter our ecosystem with items caught in the flood. Plus, with the threat of climate change, major floods are happening more often than historical data suggests. In just March 2021, South Nashville experienced some of the worst flash flooding since 2010. The neighborhood has still not recovered from the devastation. Water levels regularly change in the Cumberland after a heavy storm, so building accessible pedestrian infrastructure can be a big design challenge.

Chicago Riverwalk has public infrastructure that goes right to the water’s edge

Metro Planning, Metro Water, and the Army Corps of Engineers are exploring implementing a riparian edge framework for the Cumberland River on the East Bank. This includes strategies like “laying back” the bank by removing earth to create a wider channel and a more gradual slope for flooding to spread out. This would maintain pedestrian access to the Riverfront compared to hardscaping and flood walls.

The proposed Wharf Park design ideas consider rising and falling water levels, citing the Chicago Riverwalk as an example of well-designed pedestrian infrastructure that must accommodate flooding. Public space on the riverbank can provide double duty by mitigating damaging flooding and also increasing pedestrian access to green space as our Downtown population continues to grow dramatically.

The Imagine East Bank Draft Vision Plan showcases several key public spaces areas

By expanding the Cumberland River adjacent greenway, Nashville may finally orient its identity towards this amazing natural asset, becoming a city similar to the likes of Chicago, Boston, Austin, or even San Antonio, which touts its riverwalk as the #1 attraction in Texas. Riverfront activation highlights healthy recreation as a priority both on and off the water. In the Civic Design Center’s book, Shaping the Healthy Community: A Nashville Plan, we provide the first vision for a true “blueway” along the Cumberland with the idea for kayak kiosks at key locations. The international design competition, Designing Action, called for a specific focus on visioning the East Bank with a health and sustainability as major priorities. Scroll through the gallery below to review 20 years of East Bank visions focusing on public space and recreation that we haven’t yet showed you!

Next Steps for Imagine East Bank

The Imagine East Bank Draft Vision Plan is well over 100 pages long, so we imagine that most members of the community will not read it cover to cover like we have. We highly encourage you to read the Executive Summary, ask questions, and make your public feedback known by filling out Metro Planning’s survey. If you have the chance to attend a community event where you can speak to Planning directly (see below for dates), that is a great way to learn more about one of the largest master plans in the United States right now.

Overall, the Civic Design Center is ready for the East Bank to blossom into the new neighborhoods of tomorrow, but the best way to ensure it is a community for everyone is to continue to push Metro to make critical stipulations on the public land lease opportunities. We believe strongly in the 4 Vision Concepts in the Draft Vision Plan, but there must be accountability in order to continue to prioritize livability for all Nashvillians.

Let’s ask ourselves these questions as we respond to the Draft Vision Plan. What do we need to meet our growing population? How can we create foundational infrastructure to support a dense, transit-oriented environment? What do we want to be able to enjoy on the East Bank for years to come? How can we think outside the box from traditional design? Don’t forget to review our Guiding Principles for Civic Design!