University Connections: Part 1

By Kayla Anderson, Research Fellow

Special thanks to Mike Thompson, Anastasiya Skvarniuk, and Elizabeth Crimmins for their work on this article.

envisioning public transportation between neighborhoods

Connectivity and transportation are increasingly being recognized for their fundamental role in furthering our city’s development. However, as roads become more congested and commuting times lengthen, it is important to explore alternative modes of transportation, such as walking, biking, and public transit, in an attempt to alleviate the strain on the city’s infrastructure and improve mobility options for all Nashvillians

Elevating Nashville’s connectivity and transportation infrastructure is at the heart of much of Civic Design Center’s work, and is included in Civic Design Center’s Ten Principles of the Plan of Nashville. In 2012, the Design Center published, Moving Tennessee Forward: Models for Connecting Communities, which examines transportation and connectivity within Middle Tennessee while identifying new opportunities for development, design, and transportation options.

In Moving Tennessee Forward, Civic Design Center proposed a cross-town transit route that connected seven universities (Watkins, Tennessee State University, Fisk, Meharry, Vanderbilt, Trevecca, and Belmont) with downtown and the Nashville Fairgrounds. The proposal attempted to outline an opportunity for increased access to educational, civic, and cultural spaces around Nashville while simultaneously providing a much-needed public transportation route that avoids mandatory downtown transfers.

Following our “hub-and-spoke” roadway layout, Nashville’s transit system has historically prioritized a network and streetscaping design practice that funnels most routes into a single downtown transit hub. This network design presents significant burdens of longer ride times and increased transfers for daily riders, particularly those reliant on public transit to get to school, work, or daily appointments. Coupling this design with a lack of dedicated funding for WeGo, Nashville’s transportation agency, city, and civic leaders have faced serious hurdles when attempting to identify opportunities for increasing cross-town connectivity via public transportation.

Why we should prioritize cross-town and multimodal transportation planning

University Connections is revisiting the idea of cross-town and multimodal connectivity, anchored by Nashville’s colleges and universities. This project builds upon the work of Moving Tennessee Forward, while reflecting the rapid development and growth our city has experienced. Through this process, we take a deeper look at specific transportation infrastructure linking our universities, while highlighting those that present the greatest opportunities for increased multimodal connectivity. We also identify existing physical barriers between each institution and propose design solutions that address accessibility concerns for individuals, regardless of their mode of transportation. Finally, we propose a new cross-town public transit route that not only links several universities, but supports existing and planned public transportation infrastructure. Our hope through this work is to continue advocating for the best practice in transportation-based design that elevates quality of life for all, while supporting the central role that public transit must play in the growth of Nashville.

More than just enhancing connectivity, expanding multimodal transportation also generates positive health outcomes. Safe and inviting active transportation infrastructure decreases the risk of pedestrian and cycling accidents, thereby making transportation safer for everyone. Active transportation also presents great opportunities to be more physically active, which has been strongly correlated to reducing the risk of dozens of chronic diseases. Strategically incorporating greenery and plants helps filter harmful chemicals and stormwater, while public art instills a sense of place and community connectivity. Civic Design Center’s 2016 publication, Shaping the Healthy Community: The Nashville Plan, lays out these and many more health-promoting built environment factors, while ascribing evidence-based best practices to unique case studies across the city.

In the initial report of University Connections, Civic Design Center is focusing on South Nashville’s connectivity, highlighting two paths that support multimodal access across the three neighborhoods between the area universities. This report takes into account the history of these neighborhoods, Edgehill, Wedgewood-Houston, and Chestnut Hill, their past and present development patterns, existing conditions that both facilitate and inhibit connectivity and concludes with design recommendations to improve connectivity between the universities via enhanced neighborhood routes.

Redlining in South NASHVILLE

isolation of Edgehill, Wedgewood-Houston & Chestnut hill

Map of forts constructed during the Union occupation of Nashville. (Civil War)

Edgehill, Wedgewood-Houston and Chestnut Hill are historic African American neighborhoods situated south of downtown Nashville. These neighborhoods developed out of Union contraband camps that were established in 1862, during the Civil War and Union occupation of Nashville. The contraband camps housed fugitive slaves who were fleeing to the city for safety. The Union army employed the fugitive slaves to construct Fort Negley, Fort Casino, and Fort Morton. After the Civil War, the newly emancipated slaves remained, with additional freed slaves moving to the area. This area would eventually become the Edgehill, Wedgewood-Houston, and Chestnut Hill neighborhoods.

Entrance to Fort Negley. Photo credit: Friends of Fort Negley

Following the Civil War, Edgehill and Chestnut Hill developed reputations as working-class African American neighborhoods, attracting individuals and families from all over Nashville. Because of its proximity to the rail lines, Wedgewood-Houston developed primarily as an industrial area with a small, working-class neighborhood situation on the south end of the neighborhood.

Central Tennessee College. Founded in 1865 to serve freedmen.

Meharry Medical College originally located in Chestnut Hill later recloated to North Nashville.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the streetcar line arrived in Edgehill, attracting the attention of downtown professionals and drawing white families into the neighborhood, creating a diverse and integrated neighborhood. Chestnut Hill established its own professional population with the presence of Central Tennessee College and Meharry Medical College, which remained in the area until 1931. However, when Meharry moved to North Nashville, the professional class moved with it, making Chestnut Hill a primarily working-class neighborhood.

Workers at May Hosiery Mill

May Hosiery Mill in early 2000s. Currently being redeveloped as a members-only hotel, Soho House.

Wedgewood-Houston meanwhile continued to grow as a predominantly industrial area. In 1908, German-born Jew, John May opened the Hosiery Mill in the neighborhood. The mill complex was comprised of eleven buildings situated on six-and-a-half acres of land, and supplied socks to companies such as Marshall Field, Montgomery Ward, Spiegel, Woolworth, and Kress.

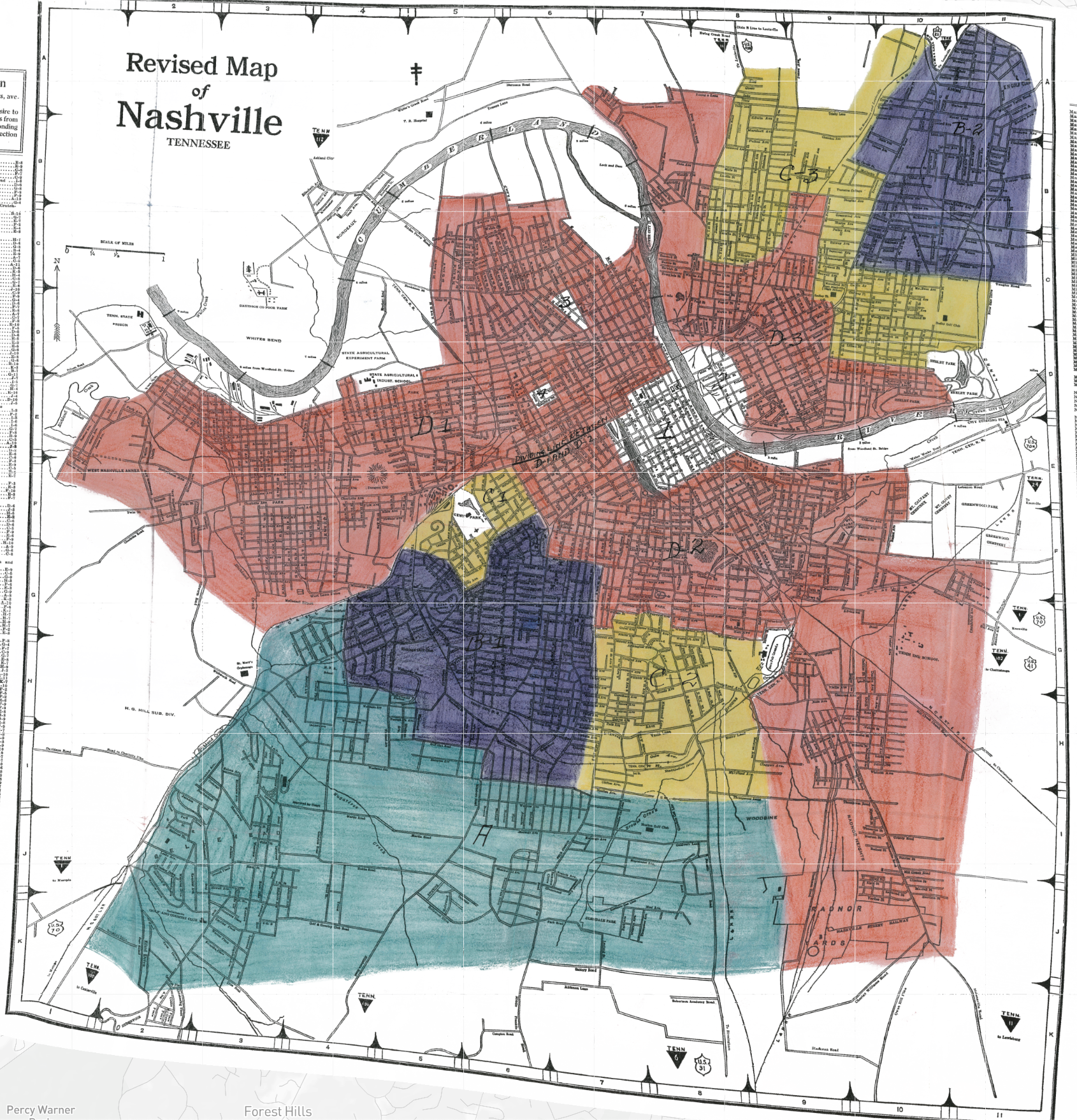

1942 Map of Nashville providing area grading determined by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. Map credit University of Richmond

Edmondson Homesite located at the present day Murrell School in Edgehill.

During the Great Migration of Southern African Americans into northern cities, more African Americans moved to Nashville and the Edgehill, Wedgewood-Houston and Chestnut Hill neighborhoods. Concurrently, the increased accessibility of the automobile at this time aided in suburbanization and white flight, as white families moved further out of the city, thus increasing segregation within inner-city neighborhoods. It was during this time that the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC), a government-sponsored corporation, was created out of New Deal policies. The purpose of the HOLC was to refinance home mortgages that were in default in order to prevent foreclosure.

It was out of the HOLC’s Research and Statistics Department, that the practice known as redlining was created. As a result of this grading practice, it became increasingly difficult for individuals to obtain or refinance mortgages in areas deemed “Definitely Declining,” and “Hazardous;” areas that were in predominantly African American neighborhoods. Edgehill, Wedgewood-Houston, and Chestnut Hill fell primarily within zone D2, an area categorized as “Hazardous,” (Part of Edgehill was also graded as “Definitely Declining”). With the “Hazardous” status placed on these neighborhoods development decreased, contributing to the economic and physical deterioration of the area. Additionally, this label prevented many African American individuals from receiving or refinancing loans, and increased segregation within Edgehill, Wedgewood-Houston, and Chestnut Hill.

William Edmondson with one of his sculptures.

During the 1940s and 1950s as white flight persisted, African American professionals continued to move into Edgehill. The neighborhood became home to prominent African American doctors, lawyers, and dentists, as well as the first African American representative in Tennessee, W.G. Blakemore. Edgehill was also home to William Edmondson, a sculptor who in 1937 became the first African American artist to have a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Urban renewal planning objectives for Edgehill, 1964 | Nashville Housing Authority (MDHA) urban renewal implementation plan for Edgehill, 1960s | Nashville Housing Authority (MDHA) urban renewal master plan for Edgehill, 1963.

It was during this time that Edgehill thrived as a vibrant African American community, boasting hardware stores, bakeries, drug stores, grocery stores, and restaurants. African American-owned businesses Clemon’s Drug Store and Patton’s Funeral Home also resided in Edgehill.

In the late 1930s and into the 1960s the U.S. Federal Government passed a series of Housing Acts intended to usher in urban “renewal”. These laws provided cities across the country federal funding for slum clearance, the development of new housing, commercial economic stimulus, and the construction of new interstates and highways. Though these projects improved needed infrastructure within numerous cities, they also displaced thousands of individuals, mostly African Americans, and abolished well established communities.

Sudekum Apartments built in 1953 as a result of Urban Renewal. (MDHA)

Chestnut Hill was directly impacted by the Federal Housing Act of 1937, as “slums” within the neighborhood were cleared in the name of urban renewal. The neighborhood was also a recipient of large-scale public housing blocks, with J.C. Napier Homes constructed in 1941, and Tony Sudekum Homes constructed in 1953, just east of the neighborhood.

Edgehill Apartments (formally Edgehill Homes). (MDHA)

The Nashville Housing Authority’s Edgehill project, funded by the Federal Housing Act of 1949, ran from 1966 to 1972, clearing “undesirable” land uses, building parks and schools, widening roads, and clearing land for Belmont University. The Edgehill project additionally created the first public housing development in Edgehill: the Edgehill Homes. These activities displaced 2,091 families, of which 84% were families of color, disrupting the lives of residents within the Edgehill neighborhood, and afflicting a previously vibrant and economically stable African American neighborhood.

1960 plan for Interstate Highway System in Nashville with key. (TDOT)

Additionally, urban renewal had a detrimental and long-lasting impact on transportation and connectivity throughout Edgehill, Wedgewood-Houston, and Chestnut Hill. The construction of I-65 and I-40 in the late 1960s cut off each neighborhood from downtown Nashville, physically isolating residents and making it increasingly difficult to travel throughout the city.

The rise of personal vehicle transportation led to the development of major arterials within the neighborhoods with the intent of eliminating congestion and limiting traffic on residential streets. Though initially attractive to residents, the lack of traffic on residential streets increased crime, and the high-speed arteries decreased safety and accessibility for pedestrians. As a result, traveling with a personal vehicle became a greater necessity for mobility, leaving behind those without the means or ability to buy and drive a car.

Traffic at the convergence of I-40 and I-65 between Wedgewood-Houston and Edgehill neighborhoods. (Nashville Business Journal, 2015)

As a result of urban renewal, and other urban planning decisions made throughout the last century, Edgehill, Wedgewood-Houston, and Chestnut Hill have become largely physically isolated from the greater Nashville community. This isolation is increased by the lack of transportation options and connectivity between the neighborhoods and the greater Nashville area. Urban renewal efforts, primarily if not exclusively, focused on improving connectivity for vehicular traffic, while forgoing alternative modes of transportation, such as walking, biking and public transit. As a result there is a lack of alternative transportation infrastructure within these neighborhoods, and a strain on the current vehicle infrastructure.

As Nashville continues to grow, this will only become a greater obstacle for individuals traveling and living within the Edgehill, Wedgewood-Houston, and Chestnut Hill neighborhoods, thus it is critical for the city to explore how to improve multimodal transportation in order to increase connectivity for all.

This is Part 1 of 4 in the blog series. There are subsequent articles published pertaining to the University Connections Project.

Jump to University Connections: Part 2

Jump to University Connections: Part 3